Witnessing History

A Young Photographer Documents a Momentous Day

Fred Stone was in college when he photographed the historic arrival of civil rights marchers in Montgomery, Alabama, in the spring of 1965. Now retired, he shared his photos with the California History Center at De Anza College. Historian David Howard-Pitney, a retired De Anza instructor, wrote the accompanying essay.

On Thursday morning, March 25, 1965, Fred Stone, then a 23-year-old college student at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, made a familiar 40-mile drive from his college to Montgomery, the largest city around and the state capital of Alabama.

The night before, students listening to radio news reports announced that “something big” was happening the next day in Montgomery. Although not particularly political, Fred was an avid amateur photographer. So the next morning, Fred and three student friends piled into his Volkswagen Beetle to drive to Montgomery and take up position downtown, planning to photograph civil rights marchers arriving at the Capitol building.

Thus, an ordinary young man became a witness to and documenter of history.

Helicopter flies over state Capitol as military police stand guard ahead of the march. (Fred Stone)

The 1965 Voting Rights Campaign in Selma, Alabama, was sponsored jointly by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) led by Martin Luther King, Jr., the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), whose chairman was 25-year-old John L. Lewis, and by local civil rights activists in Selma and nearby Marion.

SNCC’s young activists by the early 1960s were the most militant, uncompromising branch of the civil rights movement. The SNCC’s 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer had been a campaign by Black and white college students to register and politically organize African Americans in a deep Southern, violently white supremacist state. Despite the horrific violence that the SNCC workers had met – and the slow headway they made in registering Black Mississippians – the SNCC and Lewis were eager to join with other civil rights groups in the fight for voting rights in neighboring Alabama.

King’s SCLC made its major commitment of 1965 to organizing mass nonviolent demonstrations demanding that all Americans be free to vote.

Immediately upon passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act that dismantled legal racial segregation and discrimination nationwide, the SCLC pivoted to request equally sweeping new legislation to ensure voting rights. Initially rebuffed by the Johnson administration, which held that new federal legislation would be too much, too soon after the just-passed Civil Rights Act, King and the SCLC planned to put pressure on the U.S. government to act by mounting a campaign of mass nonviolent demonstrations.

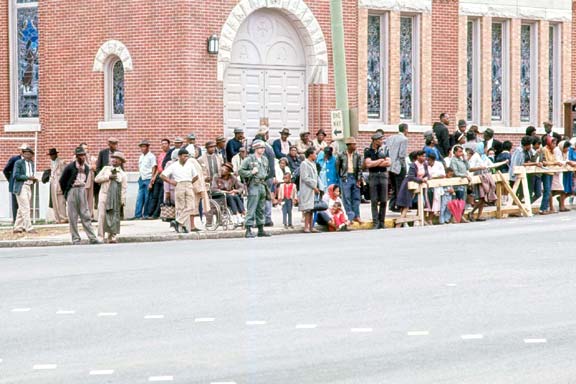

People gather along Dexter Avenue. (Fred Stone)

News cameraman readies equpment. (Fred Stone)

King would later say that the 1965 Voting Rights Act had been “written on the streets of Selma.”

The Selma protests campaign and consequent passage of the Voting Right Act was one of the greatest victories of the civil rights movement, a Black-led, multiracial movement in the 1950s and 1960s that organized many people – most of them “ordinary” and many of them young – to stage mass, nonviolent protests to pressure authorities to accept their democratic demands.

The Selma protesters sought to expose the many methods long used in the South, such as literacy tests and unannounced closings and reduced hours at registration and polling sites favored by Blacks, to disenfranchise African Americans.

This story is told in five parts:

- Part 1: Marching for Justice

- Part 2: Bloody Sunday

- Part 3: Arriving in Montgomery

- Part 4: The Voting Rights Act

- Part 5: Freedom Is Never Free

Introducing the Project

We are pleased to begin a new online series featuring stories, images and video interviews that will offer unique, personal windows into history lived and experienced by California History Center members and supporters from the communities we serve.

Meet the Contributors

Fred Stone retired from Hewlett-Packard in June 2000, after almost 24 years with one of Silicon Valley's leading tech companies. David Howard-Pitney is a historian who specializes in the thought and rhetoric of African American leaders.

Commentary

In the fight against racially based hate and fear-mongering, the California History Center can play a role by doing what it has always done – building empathy and respect for a community’s history though stories told across race and ethnicity.